Introduction to the plugin model of the new provisioning server

What must be understood is that if you install provd, but you do not install any plugins, the server won't be able to configure anything. This means that without plugins, provd is pretty useless.

Each plugin can configure devices from configuration specifications. Plugins can also offer some

additional services, like the downloading of external files, like firmware or dictionary files for

example. So what was done before by xivo_fetchfw is now partially integrated in each and every

plugin.

One important particularity of this system is that each plugin is isolated from the others. Besides,

and unlike the old provisioning server, the plugins doesn't share a common directory like

/tftpboot. This way, there's never a conflict between the files used by the different plugins, and

this make it easy to have for example a xivo-aastra-3.2.0.1011 and a xivo-aastra-2.6.0.2019 plugin

on the same server.

This means that with provd, you can have at the same time and on the same network, for example, two

Aastra 6730i, one using the 2.6.0.2019 firmware and another using the 3.2.0.1011 firmware, and this

using the same DHCP server configuration for the two devices. From the point of view of both

devices, their firmware will be located at http://<provd\_ip>/6730i.st, but for one, this

will be a firmware in version 2.6.0.2019, and for the other, a firmware in version 3.2.0.1011. And

if you are curious and point your web browser to this URL, you'll get an error 404 !

We must know that provd, unlike the old provisioning server, doesn't depend on an external HTTP/TFTP server to process the requests, since it handles these requests by itself. This was becoming necessary with the introduction of the plugin system and the 'dynamic' request processing.

Now, if you are a mentally sane person, you might be asking yourself if this whole system is based on sound principles. And I have good news for you; you are not insane, this system is not based on sound principles a priori.

In fact, for this system to becomes reliable, a precondition must be true: for each request, it should be possible to unambiguously identify which device is behind it. With this unambiguous information available, we can then look up in our device database for the complete information we have on this device, and then find which plugin should handle the request, and redirect the request to this plugin.

The good thing about this is that most devices provide this unique information. For example, the Aastras send their MAC address in the User-Agent header of each HTTP request they make.

That said, some device doesn't give as much information, like the Cisco 7900, which can only do TFTP requests. This means that sometimes, and only for some requests, the only 'unique' information we can extract from a request is the IP address. This does not generally cause problem, except if you are constantly changing the IP addresses on your network. And if you enable the provd-DHCP server integration, it will make sure that the MAC-IP association is always up-to-date, and this means the system will be reliable once again.

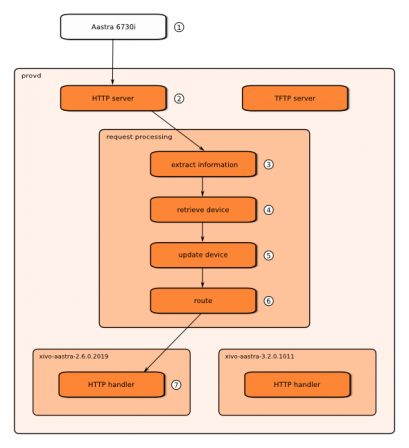

So, part of provd is only about making this system reliable and finely tunable if there's any need to fine-tune the behaviour of the system. And to make thing a bit more clear, here's a high level view of what happens when an HTTP request is made to the provisioning server:

- An Aastra 6730i using firmware 2.6.0.2019, with MAC XX:XX:XX:XX:XX:XX and IP Y.Y.Y.Y, does an HTTP GET request for /aastra.cfg to the provd server

- The HTTP server component in provd receive the request. It then sends it to the 'request processing' component. Note that TFTP requests are also being processed by the request processing component.

- The first step in the request processing is to extract information from the request. The goal is to extract the maximum of information about the device behind the request, like its MAC address, model, vendor, firmware version, serial number, IP address, etc. By default, each plugin can participate in this step. In this case, at the end of this step, we know that the request comes from an Aastra 6730i in version 2.6.0.2019, that its MAC address is XX:XX:XX:XX:XX:XX and its IP address is Y.Y.Y.Y.

- The second step in the request processing is to retrieve the device from the device database using the information extracted at 3. In this case, we suppose there was already a device with MAC XX:XX:XX:XX:XX:XX in the device database, so we retrieve it.

- The third step is to update the retrieved device using the extracted information. For example, we can update information we didn't know about the device. We can also do generic operation in this step if we need to. Anyway, in our case, this step is actually a no-op.

- The last step is to route the request to the HTTP handler that will answer the request. In our case, from the device retrieved at 4, we know that its associated plugin is xivo-aastra-2.6.0.2019, so the request is routed to the HTTP handler of the xivo-aastra-2.6.0.2019 plugin.

- Finally, the handler chosen at 6 answer the request. In this case, the xivo-aastra-2.6.0.2019 plugin will return the content of its var/tftpboot/aastra.cfg file.

Now, you might be wondering how this work when an unknown device make a request to the provisioning server. By default, at step 4, if no device can be found in the database, a new one is added.

Then, at step 5, if a device has no plugin associated to it, an automatic device association process occurs. Also at this step, a device with no config associated to it can have a default config associated to it. So, at the end of step 5, we then have a device with a default config and an associated plugin although the device was not known from the provisioning server when the request was received.

So this is what conclude our brief introduction to the plugin model of the new provisioning server.

If you are interested into digging into the details, you might want to start by looking at the

provd/devices/ident.py python source file (this make me thing I should rename this file) and the

various *.py.conf.* configuration file.

Note that to keep this text at the introduction level, some things stated here have been slightly simplified and are not 100% exact.